Why I don’t Rely on TSS

OK, I know that this is written really more for the benefit of coaches than athletes. Still, I know that some of you coaches out there may be reading this, and many others are self-coached. In any case, here we go (this one is a bit lengthy):

First, what are we talking about? Before you go running around with your TSS status, thinking you’ve got the holy grail of training and performance in your pocket, read on.

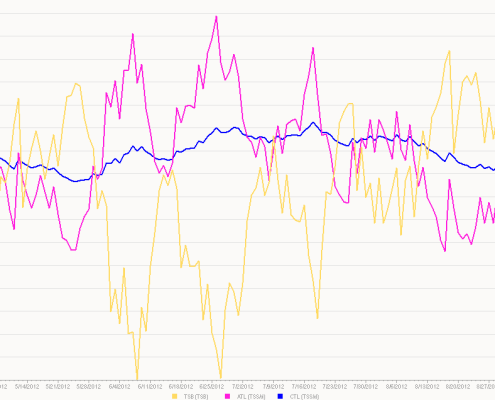

What the heck is “TSS” – (Training Stress Score) is a numerical value assigned to any single workout or race. It’s intended to directly measure the “training stress” – or the physiological cost of that specific event. It is based on an algorithm using your threshold levels, measured via a common metric such as power (Watts) or pace, the duration of the session, and a little math. It accumulates from day-to-day, week-to-week, even month-to-month, depending directly upon how often, how long and how hard (intensely) you work. To measure it over time, we (i.e. a software program) run 7-day, and 42-(or more)-day moving averages. These are called “acute training load” (ATL), and “chronic training load” (CTL), respectively. By tracking these together over time, a coach or athlete can theoretically measure fitness, fatigue and “form” (race readiness). You get a chart that looks like the one below, called a “Performance Management Chart” (PMC). Pretty valuable right? Well, maybe.

Performance Management Chart

- The primary reason I do not rely much on TSS is that it only attempts to measure “training stress.” It does not measure life stress. You know, the stuff going on in your life the other 20 or so hours a day when you’re NOT training. What about that? It’s up to you to measure.

- It is a loose approximation at best of actual physiological stress on the body.

- Everyone responds differently to different training stresses. For example, an 11 mile, 90 min run for 2 different athletes with the same running profile (threshold pace) will produce similar TSS scores. However, it takes no account of individual strengths and weaknesses. If one runner is highly aerobically oriented and fit, durable, and experienced, while the other is anaerobically oriented, maybe better on hills, better at speed-work, (perhaps a sprinter by training), the impact on these 2 athletes is very different, even though their TSS scores will be very close. (Yes, these 2 runners can have the same Threshold Pace.)

- It ignores harder to measure factors, such as re: swimming; What about open water conditions? Swimming a mile in a pool vs. open water can be easy vs. brutal (at the exact same pace). It also relies too heavily on HR in the absence of a power data (bike), and pacing info for an entire run, or swim. (The “TRIMP score”).

- It assumes that your FTP, T-Pace (swimming), and Threshold running Pace are in fact accurate. Yet, they are always moving targets, and vary up and down (rather quickly) according to how fit and fatigued an athlete is at any point in training. So, a ride with a TSS of 150 on one day is very, very different in terms of physiological cost (what it purports to measure directly) compared to another day, or from one side of a whole training block to the other. That is, TSS does not factor in an additional measure of accumulated stress (ATL or CTL, the metrics tracked) for any individual workout. In other words, a workout with a TSS of 150 is counted the same, whether or not you do it fresh and rested at the start of a training block, or pretty much fried at the end of the block. (Another reason why I argue that TSS moves much more on a daily basis than we account for.) This is the job of the athlete and the coach working together.

- Again (and so important); TSS totally ignores the rest of your life: rest, sleep quantity and quality, nutrition (a HUGE FACTOR), hormonal (im)balance, relationship, family, and job issues, underlying health issues (not directly related to fitness). It misses big, and critical – arguably the most critical – variables.

- It is backwards looking by design, and therefore, not necessarily a good predictor of how ready an athlete is to train hard, (or even what to do) on any given day. That comes down to projection, a game which is, well, a guessing game (even for the best statistician).

- And one of my favorites; That which is measured is NOT necessarily improved. Just because we can measure something, does not mean we can change it for the better, or at all. I can measure how tall I am. I can measure how many fingers and toes I have. I can measure other more mutable characteristics like fasting blood sugar, HDL/LDL count, HbA1C count, blood pressure, and body fat %, FTP in watts, and my average HR at my 10K race pace. Nevertheless, I may have no idea whether or not the numbers I get are good, bad, indifferent, or irrelevant to my goal.

I’ve had athletes perform exceptionally well when their PMC chart predicted they were fatigued and not ready for a good performance. On the flip side, I’ve had athletes whose numbers were optimal on the chart have flat and mediocre days, only to excel at a different, less optimal point on the same chart.

What’s the take away? Trust your own instincts working with your coach, and learn to intuitively feel your own fitness, fatigue and race readiness without the use of a rigid and narrowly focused PMC chart.

Don’t get me wrong, TSS is useful. Just probably not as useful as it appears. I still use it to help guide my coaching, but just not in isolation. When used in its proper context, it can be pretty useful. However, that context is becoming smaller and smaller, the more I discover what it is that TSS actually does measure.